Wellness and the mobile workforce

by Dr Nhlanhla Mpofu, Medical Director of Occupational Health at International SOS

WHO defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity1.” Extending this definition of health has changed the traditional societal notion of a ‘healthy person’ from one who has regular exercise, eats well and regularly visits their doctor to a holistic and functional individual influenced by their choices, lived experiences and the environment they live and work in. This is what determines ‘wellness’, an individual’s optimal state of health.

Multiple dimensions contribute to this holistic definition of wellness which includes: occupational, financial, physical, intellectual, social, environmental, psychological and spiritual dimensions. There is growing evidence showing that it is the continuous interaction and balance of these wellness dimensions that help individuals reach their potential in their families, community and workplace.

Business travel or international assignments have the potential to change any or all of these dimensions and their interconnectedness, and ultimately affects an individual’s wellbeing if not deliberately managed. This article will explore how business travel or international assignments impact psychological and physical wellness dimensions.

• Physical wellness focuses on sustaining a healthy body. It includes being in tune with one’s health and recognising signs or symptoms of illness.

• Psychological wellness encompasses the ability to understanding one’s feelings and cope effectively with stress. While minimising stress where possible is important, it’s impossible to eliminate entirely. One can nurture their psychological well-being with regular self-care, meditation and other forms of relaxation or stress reduction. Being able to learn and grow from both positive and negative experiences is essential.

How work travel affects wellness

The exposure of business travellers and expatriates to the risks associated with population movements has been shown to be associated with increased risks of psychosocial disorders, reproductive health problems, nutrition disorders, drug and alcohol-related disorders and an increased vulnerability to non-communicable diseases (NCDs)2.

Expatriates have been shown in what is known as the ‘healthy migrant effect’ to be ‘healthier’ than local residents on first arrival in a new country, but over time, their health advantage diminishes and they end up in worse health3. The initial status can be attributed in some extent to a deliberate selection process that may include different levels of medical, psychological, social and occupational screening pre-assignment such that only assignees in good general health are deployed. Once in a different location or country, individual, social and workplace factors interact causing the disparities in the mobile workforce well-being.

Well-being risk factors

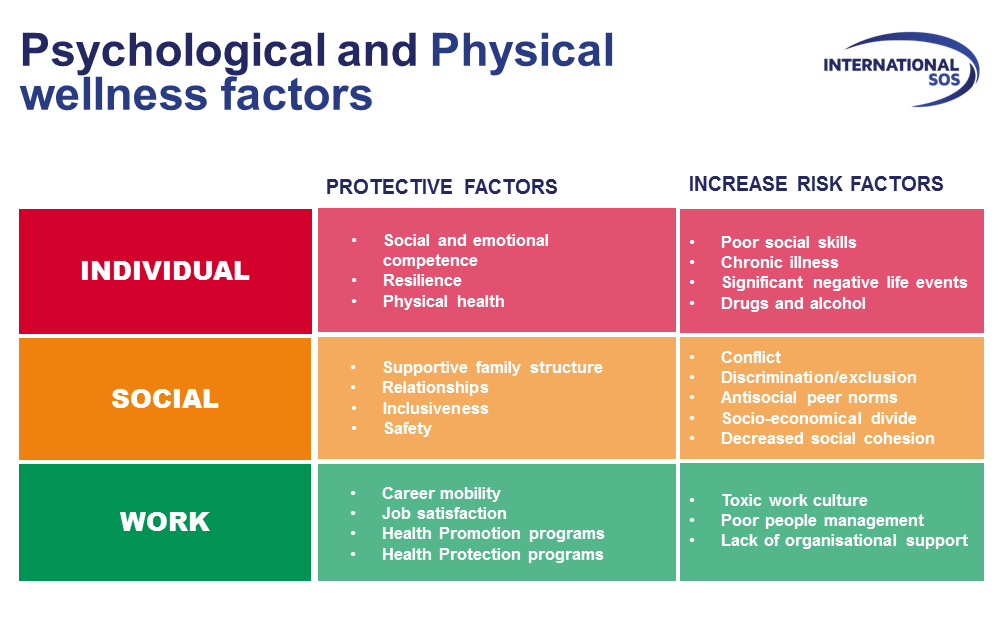

Figure 1 shows psychological and physical wellness risk factors that can have a protective or detrimental effect on individuals, especially during business travel. On an individual level, people can have varying degrees of social and emotional competence, resilience and physical health (fig. 1). These are protective risk factors that are likely to help people positively cope, manage and thrive, especially when travelling. Risk factors that increase the likelihood of negative well-being especially when travelling include poor social skills, chronic illness, significant negative life events, drugs and alcohol.

From a social perspective, protective risk factors include having a supportive family structure, fulfilling relationships and a sense of inclusiveness and safety. Components that could negatively impact well-being include conflict, discrimination or exclusion and antisocial peer norms.

Workplace factors

Regardless of if employees work full-time or part-time, work remotely compared to being in the office every day or travel on a regular basis, organisations play a vital role in employee well-being.

While each person is responsible for their own actions impacting wellness, employers can influence the work environment and social setting during business travel and have even greater influence when on an international assignment.

While employers have a moral and legal duty of care to protect their employees from foreseeable risks that carries outside of office walls and even country boundaries, they can further support their mobile workforce by:

– ensuring their employers are medically fit for work

– having up-to-date health protection and health promotion policies that focus on prevention5 and can manage destination-specific diseases (endemic diseases) and encourage healthy behaviours that mitigate non-communicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs such as diabetes, osteoporosis and heart disease can impact productivity, health care costs and morbidity, as well as impact travel. NCDs were once said to be diseases for the rich, but they are quickly becoming prevalent throughout the world.

– giving employees a balance of job opportunities, job control and job satisfaction which increases psychological wellness

– pro-actively managing negative work culture and poor management

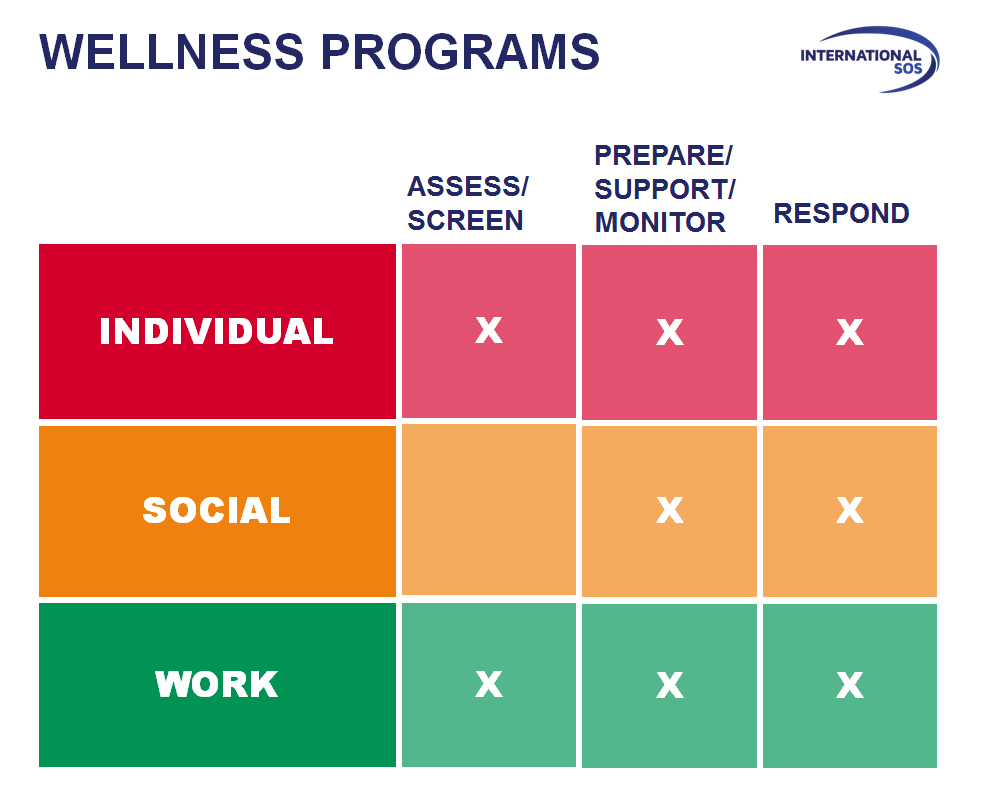

Organisations should establish wellness programs that support and encourage holistic health. This can be done through assessments and screenings; preparing, supporting and monitoring individuals; and responding quickly and appropriately if a situation arises (fig. 2). These measures are even more critical for business travellers and international assignees, as they could be away from home and their regular health care team when a medical issue occurs.

By investing in occupational health programs, organisations can show their duty of care while safeguarding both their interests and their employees’ well-being. A cost-benefit analysis showed that $1 invested in medical check programs had a $2.53 return, and the cost of a failed assignment can reach up to USD$950,0004.

Resources

1 Constitution Of Who: Principles. http://www.who.int/about/mission/en/

2 Zimmerman, C., Kiss, L., & Hossain, M. (2011). Migration and Health: A Framework for 21st Century Policy-Making. PLoS Medicine, 8(5). doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001034

3 Anikveena O., Bi P., Hiller J.E., Ryan P., Rodger D., Han GS. (2010). The health status of migrants in Australia: a review. Asia Pac J Public Health, 22(2):159-93. doi: 10.1177/1010539509358193

4 Return on Prevention study by Ipsos MORI and commissioned by International SOS. https://www.internationalsos.com/return-on-prevention

5 Gushulak B. and MacPherson D. (2004). Population Mobility and Health: An Overview of the Relationships Between Movement and Population Health. J Travel Med, 11(3). 171-4.